Every so often, an unspectacular technology comes along and quietly changes the face of the planet. Knotted strings and sticks pressed into wet clay helped us remember promises made and kept, birthing concepts like trade and debt. Small metal discs gave kingdoms the power to transcend relationships in trade and finance armies, changing the stories of entire cultures in a moment. Banking and double-entry accounting gave Mediterranean traders new eyes with which to see commerce, allowing greater understanding of business operations and eventually helped pave the way for explosive industrial growth in the past several centuries.

These seem like such tame technologies; all they do is help us keep track of numbers. And it can be argued that they merely reflect the values of the cultures that created them. But as the unknown sage says, “we shape our tools; thereafter our tools shape us.” As a lens through which we see the world, they both enable and push us to affect the world, sometimes violently, according to their numerical, linear logic. Every externality — every ecological or social cost shouldered by the commons — simply doesn’t have a place on the books.

I don’t honestly think that bookkeeping practices are the sole cause of depleted fisheries, desertification, income disparities, polluted air and water, and increasing atmospheric CO₂ levels, but I do find it telling that there isn’t even a place in our balance sheets for the imbalances we cause.

But what if there were ways to account for, and more consciously see, environmental and social externalities? And what hidden opportunities might appear when everyone has a clearer view of the people, resources, and processes that make up the whole of our geographic, economic, political, and social activity?

This article explores a nascent technology that gives us a new lens through which to look at the world, and three groups that plan to use it in an effort to create more integrated and innovative ways to provide for human needs within the current system. hREA is a software toolkit, built on Holochain and based on the Valueflows economic vocabulary, itself based on a seemingly unspectacular but quietly innovative accounting standard called Resources, Events, and Agents (REA).

hREA allows developers to build economic and financial apps that take a zoomed-out view of the economy, allowing us to see the ecosystems within it and recognise its place within the biosphere. This happens in two ways: first, economic activities are situated in a network view, breaking down silos around people, organisations, and locations; and second, it can track multiple forms of value as they flow through exchanges, regions, and production processes.

In other words, it helps us focus our economic lens more clearly on the deeply networked world we live in, so we can optimise our resource use with an aspiration of living in harmony with nature.

Code A: Giving the ecosystem a stake in the economy

Dr Leanne Ussher is an economist who works with Code A, which is short for ‘Community Decision-making for Ecosystem Adaptation/Accountability/Action’. It’s a project created by an international group of professors, and it aims to build tools that help communities understand and be more intentional about their impact on the planet. And because the economy’s tendrils are woven through every aspect of our society and environment, part of this work means developing a much more accurate way of seeing our economy within its geography.

Traditional economic models assume an ideal person — Homo economicus — who makes rational decisions about what’s best for them. And what’s true of an individual, they reason, is true of the sum of these individuals, or the economy: given a whole marketplace of these mythical self-interested, intelligent decision-makers, things will settle into the most beneficial situation for everyone. Philosopher Adam Smith called this the ‘invisible hand’ of the market, and many economists since have grounded their economic theories on a faith in this principle. And things do seem to work this way — for simple, competitive markets that we make easy to understand.

But that’s not true of most real markets. Dr Ussher’s complaint of traditional macroeconomic theory is that it assumes individual independence. This simplification supports aggregation and generalisation but it can’t anticipate the complex and surprising things that happen when a bunch of individuals get together and interact. At best, it vaguely asserts that scale does not matter and a description for an individual is also a description for a market. But in reality, we see this theory break down in catastrophic ways in an unequal world; it seems that the invisible hand has always had tremors.

My hunch is that the economy has become too large, complex, and dominated by big players for anyone to make truly rational decisions in their own self-interest. How do I make sense of whether my smartphone purchase is going to come back to haunt me and my grandchildren? It’s merely one among 1.5 billion each year; does it really contribute that much to civil unrest in Africa, pollution in China, and increased CO₂ levels all around the world? But then again, I recognise that “no individual raindrop considers itself responsible for the flood”. In our acceptance of the sole moral guide of economics — does it benefit me — it seems we paradoxically end up doing things that are very, very bad for ourselves. And even if we’d like to excuse ourselves, we’re often unsure how — life in the global north all but demands that I own one of these stupid smartphones.

Post-Keynesian macroeconomics, a branch of economics that gains insight through accounting equations of an economy as a whole, attempts to correct for the flaws in microeconomic theories of independent individuals by recognising that complex systems are always greater than the sum of their parts. It creates models founded on theories of the entire economic system, populates those models with big aggregate data, and uses the output to inform policies of regional and national governments and international trade.

This is the school of thought that Dr Ussher comes from. But she also acknowledges that there are blind spots in such a theory too: its abstract models and aggregated data sets take a big-picture view, and it doesn’t offer an explanation or prescription for individual behaviour. As such, it doesn’t tell us how we can organise our individual decisions for better global outcomes.

Dr Ussher explains that micro- and macroeconomics both have their place, but they’re taught as separate classes in university and there isn’t really any good way to reconcile the two. It would be great, she says, if there were something that could combine the micro’s individual behaviour approach with the macro’s systems thinking lens. A sort of ‘grand unified model’ for economics.

Then she says something that surprises me: Valueflows, the economic grammar at the heart of hREA, offers a path in this direction. It records the flow of resources between individuals, but it records them from an independent view — as a transaction between parties rather than a set of entries in two disconnected ledgers. She claims that this bookkeeping ‘in the open’ is the thing that could align macroeconomic models more closely with the reality of interdependent individuals. And while she acknowledges that this could have serious consequences for privacy and autonomy if done wrong, she’s also thrilled about the immense potential if done right.

At this point, my mind begins to drift back home — could this be useful at the micro level too? If global markets are inefficient because we lack information and power, could Valueflows make more local flows visible, helping us make better decisions in the places where our choices matter? If we could all see unmet needs and unused resources around us, perhaps new businesses would emerge to close those gaps. This would in turn bring the feedback loops between our actions and their consequences closer to home, giving us even more information for wise decision-making.

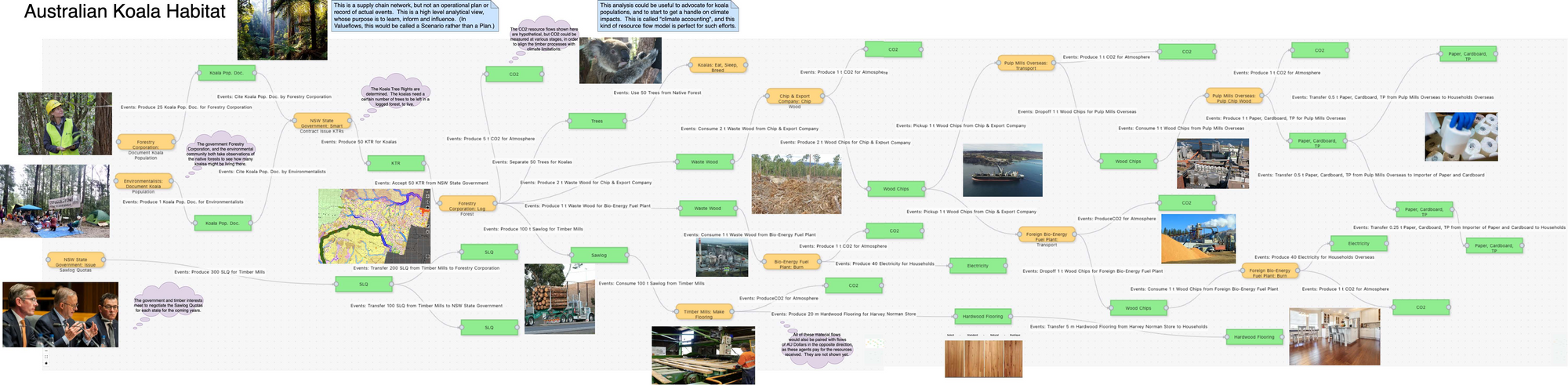

Dr Ussher’s vision goes beyond mere commerce. With Valueflows, individuals, households, corporates, and governments are not the only agents that make choices and are held accountable; trees, rivers, animals, even the atmosphere could be represented as agents, with rights, duties and decisions via carefully designed smart contracts. As we build an accounting ecosystem of agents, resources and processes with a rich body of shared data, we will be able to see more clearly how our individual — and collective — decisions impact our planet and each other.

With this vision, she hints at a much broader concept of the popular term ‘metaverse’. Rather than mere escapism underwritten by advertising money, Valueflows could equip it to become a tool for creating ‘digital twins’ of agents (human and non-human) and resources (artificial and natural, concrete and abstract) and giving them legitimacy in our economics systems.

For my own pedagogical purposes I define the Metaverse as a digital twin of the real world. We have been in a Metaverse of sorts for decades. The Metaverse can be much more than a 1:1 mapping, just as the real world can be more than a 1:1 mapping with the Metaverse.

— Leanne Ussher (@LeanneUssher) October 27, 2022

Given that legal and financial systems are already digital, mapping and controlling our behaviour, she asks whether it’s really such a jump to empower a tree with its own digital presence in an economic metaverse — and endow it with its own agency. This is what excites her most about Valueflows, because it carries the promise of including all entities that we regard as important, holding all participants accountable, and designing features to rebalance inequities in market power, rights, and duties. By giving the biosphere rights, we can internalise externalities. This is nearer than you might think — legal systems are already recognising bees and rivers in this way.

Recently Dr Ussher was supporting a cohort of students at Simon’s Rock Bard College with exercises involving coordination of student tasks in the campus garden and collecting kitchen waste for composting, or designing a new accounting protocol to reduce Australian deforestation and biodiversity loss.

In these exercises, the goal was to use a Holochain app called REA Playspace, a canvas that allows them to create models of an economic network. Spread out like this, poorly managed resources (things we might call ‘externalities’) and unserved needs are plainly visible. This can spark spontaneous insights into ways to improve the circularity of resource flows, design feedback loops that promote biodiversity, even create business opportunities along the way.

Dr Ussher still plans to use hREA in real on-campus pilot projects. As they progress, she hopes that their reach will quietly, slowly expand to include more local economic activity. Like leaven in the dough, the idea of deep wealth could eventually permeate and transform the way we do accounting, and how we hold each other accountable.

NY Textile Lab: Putting designers at the front of the supply network

Laura Sansone is a textile designer and Adjunct Professor of Sustainable Textile Design at Parsons School of Design in Manhattan, NY. When she moved to the Hudson Valley, about an hour north of New York City, she became good friends with the orchardist who leased her new property. She saw him selling his produce at a farmer’s market in NYC one weekend, so they got to talking about local food systems. She started to wonder — why do we care so much about local food systems but barely talk about local textiles? After all, the local food movement was all about understanding and improving the impact of the way we eat, so why don’t we have a similar relationship with what we wear? Her intimacy with the textile and fashion industry, which harms us and our planet, told her that it could stand to learn a lot from the local food movement.

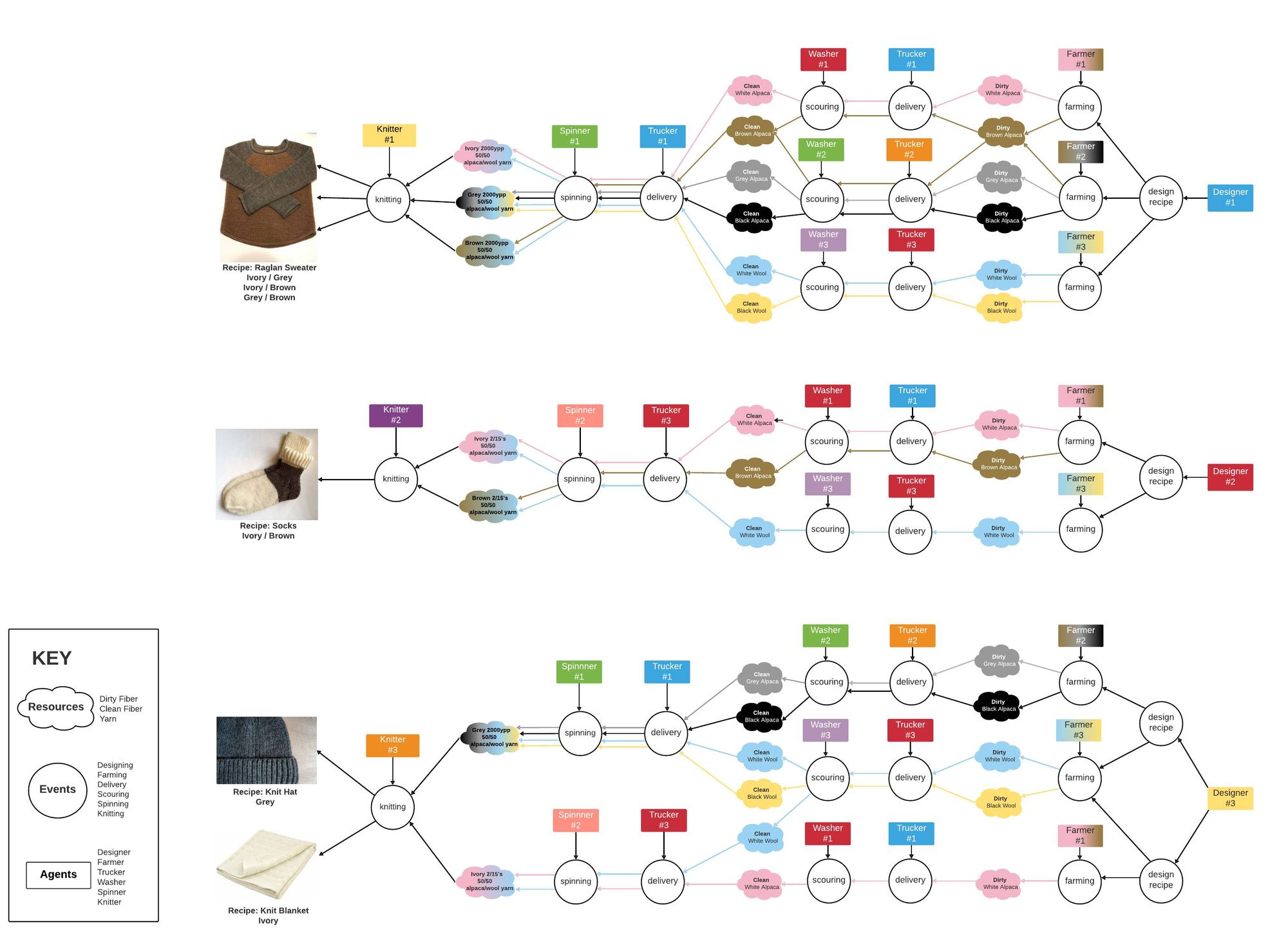

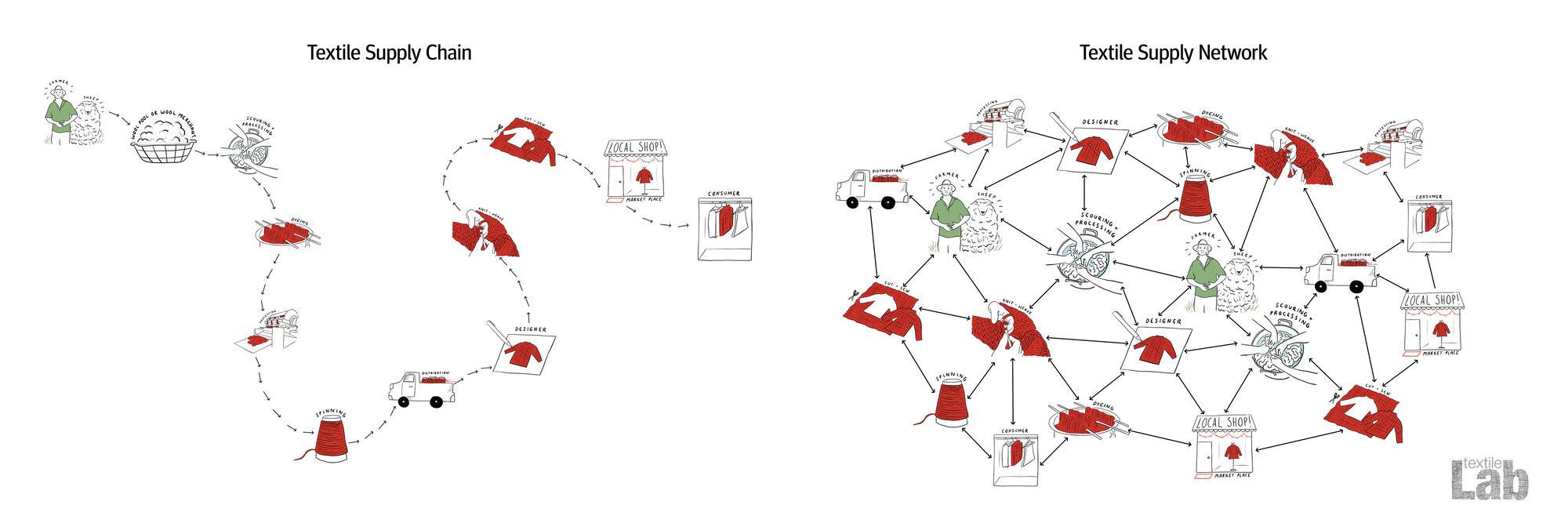

Sansone came to realise that relocalising clothing production is a good deal more challenging; there are a lot more people between a sheep and your sweater than there are between a tomato plant and tonight’s dinner. As a textile designer, she found herself at the very end of a network of producers, processors, and distributors who had already made their own decisions about what materials she could work with.

So she put herself at the front of the supply chain. As a designer, she reasoned, she would have the power to make impactful choices if she could be involved in the whole process. Starting small, she aggregated wool from several small local farmers, transported it in a borrowed pickup truck, and brought it to the few remaining wool processing facilities in the New York bioregion — one of which was just a farmer with a handful of washing machines in her garage to wash the animal fibers.

This wasn’t meant to turn into a business; it was just supposed to prove that Sansone’s idea for a local textile economy could work. However, she soon found herself selling her yarn to other designers, and eventually creating a line of finished products for sale.

But Sansone didn’t want to become the distributor she was trying to eliminate.

Now, at the centre of NY Textile Lab, a small but growing collaborative network of producers, processors, and designers, she and her partner Evan Schwartz need something more than an address book and a pile of spreadsheets.

Sansone and Schwartz were attracted to hREA because it’s expressive enough to model the complexity of the rich web of relationships they’re weaving. They intend to record details about the raw materials and the processes they went through, such as transport miles and climate-beneficial verifications, so customers can see exactly what went into their garments. They also want individual designers to be able to merge their buying power, simplifying procurement and reducing costs for everyone.

With this complexity comes a lot of administration, so they’re looking forward to using hREA to automate most of that. As a generic toolkit that uses a simple ontology for building all sorts of economic applications, it can be used for bookkeeping, inventory, supply chain management, certification tracking, enterprise resource planning, alternative currencies, and even sharing of production process recipes.

Listening to Schwartz explain their vision, I wonder what the value proposition is for designers. It sounds like they might struggle to understand why they would want to be more transparent, choosing to give up the competitive edge that supply chain trade secrets give them. He answers my concerns before I even voice them: This isn’t meant for the Ralph Laurens and Patagonias out there. They already have their supply chains in place, and they’re already working to answer customers’ demand for more visibly ethical sourcing.

This is meant for small designers and light industry, in order to grow a more horizontal economic model — the recent design school grad who’s starting her brand with a production run of only 20 sweaters, the small farmer only raising a few dozen animals, the ‘mini mill’ that is currently serving ‘handcrafters’. These people currently don’t have the power to compete in the same way; the landscape of potential suppliers is challenging to navigate, and as individuals they don’t have the ability to meet minimum order quantities, nor the purchasing power to make their production economical. The patterns Sansone and Schwartz are building are giving these smaller designers the ability to enter the market — as well as giving sustainable livelihoods to local farmers and regional processors.

Listening more deeply, I realise that they’re actually building an open-source economic model for the textile industry — and local markets in general. In the logic of this economy, everyone succeeds when supply chain relationships and other intellectual property are shared. And Sansone and Schwartz plan to share their templates as they evolve, enabling other local production economies to spring up across the world.

And more than that — they’re building an economy that functions ecologically. Ecosystems don’t usually create chains, because chains are only as strong as their weakest link. Instead, ecosystems create webs — complex patterns of relationship with multiple interdependencies and redundancies. Schwartz claims that this is the way to build supply systems that are resilient in the face of disruptions. And goodness knows we could use a bit more of that.

Sensorica: Applying open-source practices to material production

NY Textile Lab isn’t the only one building an economy that understands the ecosystem it belongs to. For the last eleven years Sensorica, producers of electronic hardware, has been operating as what’s known as an open value network, or OVN. Rather than a hierarchically organised company, an OVN is a decentralised network of economic agents, each of them free to do their own thing but linked to each other by collaborative relationships.

Tiberius Brastaviceanu, the co-founder of Sensorica, tells me that they borrow ideas from self-organising systems such as insect colonies. Most importantly, their network operates on a few simple rules that produce complex — and ultimately meaningful — behaviour.

The first rule is this: you can do whatever you like, but whatever you do, make it visible. Announce it and document it. If you’ve got a 3D printer, make it available. If you’ve come up with a design for a more efficient heat recovery ventilator, share the source files along with your research process. That lets others build on your offerings and increase the total value in the system.

Biologists who study insect colonies came up with a word for this: stigmergy, or ‘leaving signals in your environment for others to act on’. This appears to be the chief principle that makes self-organising systems work. Although it may seem chaotic, the end result is not. I mean, just look at what these bees created without a boss. (It’s actually a myth that the queen is in charge.)

Brastaviceanu echoes Dr Ussher’s concerns about the privacy and autonomy issues that crop up when we aggregate so much of our data like this. But he believes that Holochain resists this risk by embedding an ethos of ‘data commons’ — a democratisation of knowledge, through a peer-to-peer database, that prevents big players from capturing that knowledge and controlling access to it.

There are other rules that draw inspiration from nature, such as the right to raise a red flag if you see someone doing or proposing something that could harm the network.

But one rule comes directly from traditional economics. All relationships are underwritten by something called a benefit redistribution algorithm, an agreement that defines how benefits will be distributed in a venture. For example, when your product is exchanged for money, the proceeds get distributed, not just to you but also to the equipment operators, designers, and parts suppliers in the OVN that sit upstream of the product. Before that point, all those contributors are shareholders; after that point, they all get their dividends. You can think of it like a stock, but for an individual sale rather than an entire company.

You’d be justified in thinking that this sounds like a lot of data to keep track of. That’s why Sensorica is a key supporter of hREA, which was explicitly designed to keep track of complex agreements and resource flows involving multiple forms of resources.

In fact, Brastaviceanu explains that the design of Valueflows is based directly on learnings from the first version of their software, called Network Resource Planning or NRP. Lynn Foster and Bob Haugen of Mikorizal Software created it from scratch, because traditional enterprise resource planning (ERP) and accounting software focuses on a single company, not a network of actors. Now Foster and Haugen are stewarding the creation of an ecosystem of Valueflows-based tools, many (though not all) of which are built on hREA.

Because it uses Holochain, hREA is doing to NRP’s software architecture what NRP did to ERP’s economic assumptions: it breaks down barriers and connects actors together. There is no server in a Holochain app; each user simply connects to other users’ machines to share data and make transactions. And when two networks want to start interacting with each other — as in the case of Sensorica collaborating with a copywriting community in Brazil — the barrier is low, because each participant has full access to the data in the spaces they belong to. This lays the foundation for highly interoperable applications.

Brastaviceanu tells me that one of the things about Holochain that excites him the most is the capacity for groups to create their own applications by connecting smaller components into a greater whole. This is exemplified by a groupware application ‘container’ called We, which already has a few simple components and expects to add many more (including ones for hREA and reputation intelligence) in the future.

Brastaviceanu believes that cooperative producer networks will only succeed in the global marketplace if they have the tools to capitalise on and grow their ‘collaborative advantage’. He sees open-source software like hREA and We as critical tools to help make that dream become reality.

Conclusion

Reflecting on these three stories, the overarching theme I see is that our narrow focus on self-interest has blinded us to the massive possibilities available to us when we start cooperating — not accidentally as puppets of Smith's invisible hand, but with intention. The fact is, we all end up better when we choose to work together. I know that sounds like something you learned in kindergarten. But it seems we unlearn this as we grow up, and it's time to relearn it.

These three projects, along with a handful of others in places like Sweden and Colombia, are courageously building economic experiments based on what they learned in kindergarten, and it’s working. And hREA, having reached its first major milestone release, is getting prepared to power the economic intelligence behind all of these projects. It's working and ready for developers to hack on, as seen in this demo video.

Some of these projects are already sturdy saplings while others are still seeds. But I see in them all a promise of something different for our world — economies that unify local production with global concerns, that apply the cooperative logic and transparency of open-source to business, that re-internalise precious externalities, and that honour diverse forms of capital.

And I long for that ‘something different’. In fact, I think our survival depends on it.