Forty-nine degrees Celsius outside. Suddenly, the climate crisis felt pretty real.

As I started writing this article back in June, sweltering in my home office, western North America was in the grip of a bizarre and unusual heat wave. One town a few hours west of me broke the all-time Canadian record at 49.6°C (121°F), and was incinerated in a wildfire later that week.

The last decade has seen more than its share of wildfires up and down the west coast; some years I’ve forgotten what it was like to breathe clear air and see the stars. Meanwhile, Germany, Belgium, and the southwest US were drenched in catastrophic floodwaters.

This isn’t normal.

I usually have to experience something myself in order to really appreciate it. It takes me from “of course I care, in an abstract way” to “holy cow, we’ve got to do something about this.” I expect a lot of us work that way.

So what can we do?

I’m not sure. But one thing I do know is that we have enough science to diagnose the problem and solve it. On the front end, we need to stop releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere; on the back end, we need to stop damaging our planet’s lungs. We can rapidly repair and even enhance our planet’s capacity to support life with the tools we already have available. And if we do it right, we could even rebalance inequity and improve the quality of our food in the process.

What we don’t know is how to coordinate our efforts — all 7.9 billion of us, and counting — to reach these goals. In a recent interview, thinker and futurist Daniel Schmachtenberger argues that if we can solve this problem, all the other problems will get solved automatically.

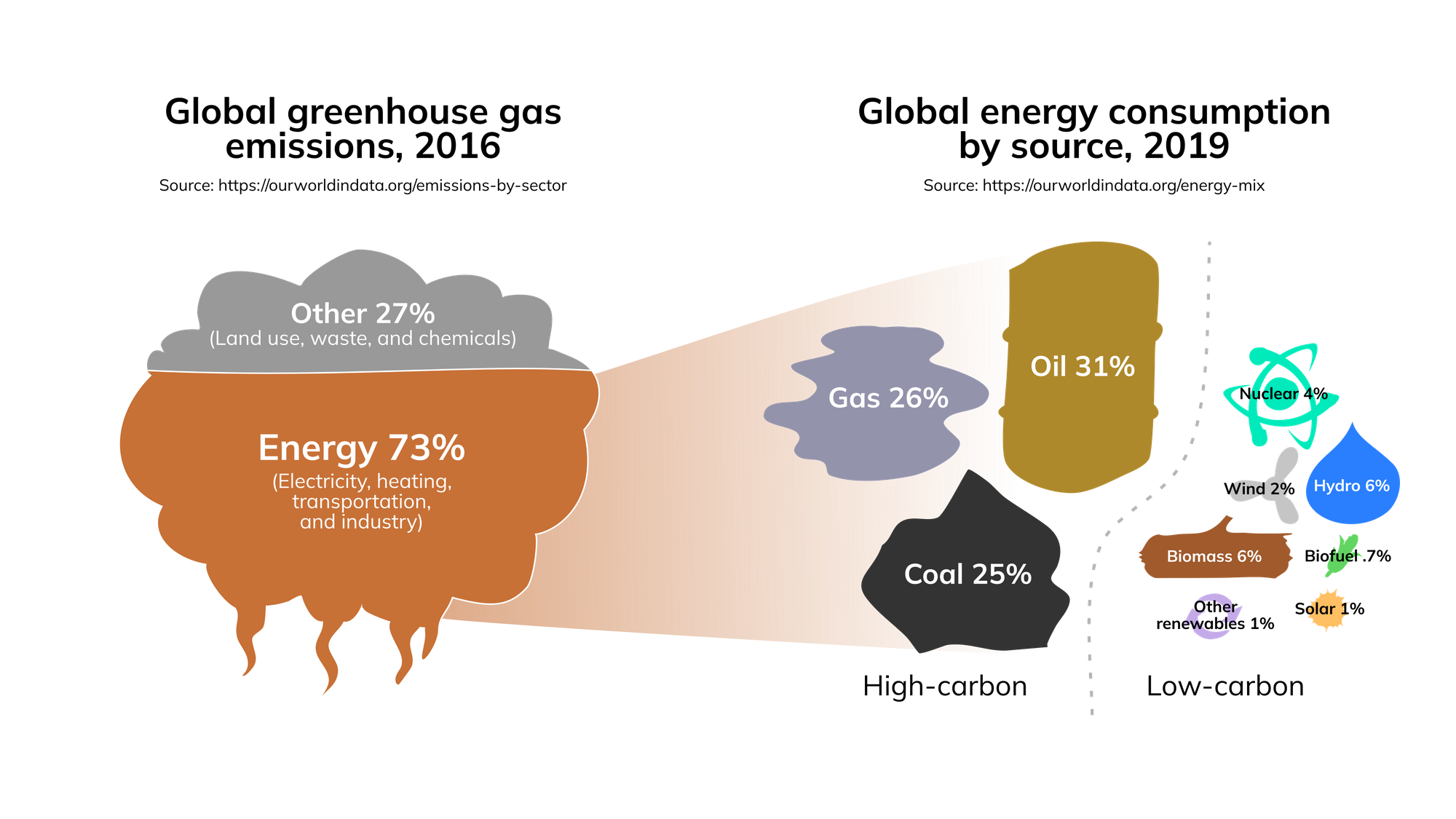

Energy, one piece of the pie

All the brightest and darkest things in our modern civilisation come from our capacity to harness the energies of the universe. And right now most of those energies come as fossil fuels — coal, petroleum, and natural gas. Almost three quarters of the greenhouse gases we emit come from energy production. That’s because 82% of that energy comes from fossil fuels. And we’re using more and more energy each year.

This tells me two things: we need to learn how to use less energy, and the energy we do use must come from low-carbon sources. As far as we know, that means we need to electrify everything.

But low-carbon electricity carries a new set of coordination problems.

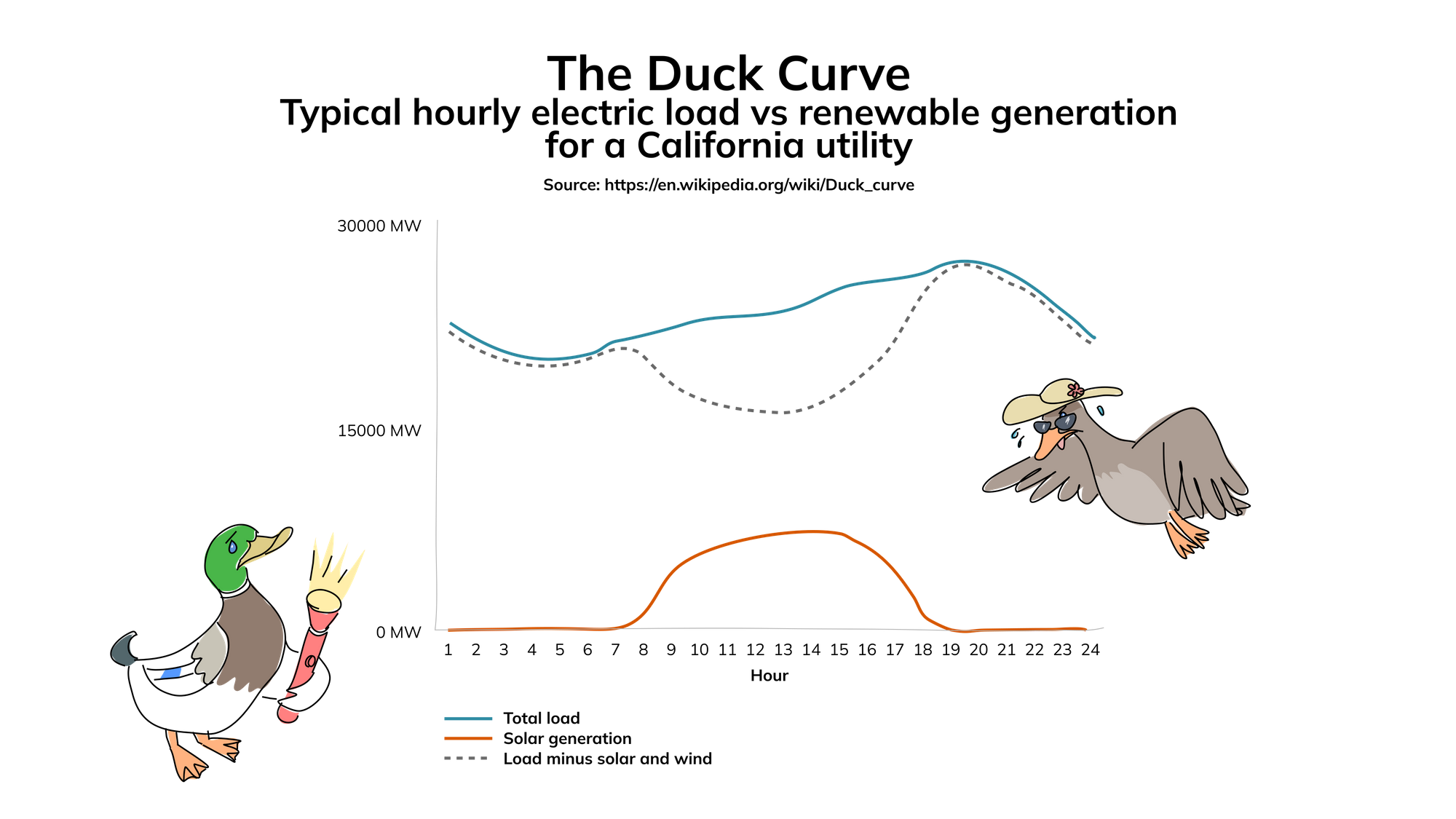

First, most renewables are not well-matched with demand. Let’s take a look at solar electricity. When we start brewing our morning tea, the sun is still rising. Then there’s a sort of peak production — too much power in the grid — in the middle of the day when we’re off at work. In the evening, just when we’re cooking supper, the sun is already going to bed. It won’t do us any good to switch to renewable electricity if it’s not actually there when we need it.

Second, power producers and distributors build their infrastructure to meet peak demand, not average demand. If we electrify everything, that would mean more drastic peaks, which would mean more power plants and fatter wires. And every tonne of concrete and steel, every kilometre of copper wire, every wind turbine, every hectare of solar panels, is the product of carbon-intensive manufacturing processes.

Third, consumers are also becoming producers, and it’s happening quickly. Over a fifth of Australian homes have rooftop solar panels, and minigrids and community solar gardens are on the rise. Distributed energy production is already here. That’s wonderful, but the grid is designed for one-way delivery of electricity generated by large plants whose output is easy to predict.

Our infrastructure isn’t prepared to handle these challenges. It’s big and unwieldy. Teaching it to respond to these new demands would be like teaching a team of oxen to fly like a flock of starlings.

But starlings are exactly what we need. Many small energy producers and consumers, responding nimbly to each other, moment by moment. Analysts tell us that the most reasonable way to do this is to decentralise and digitalise the grid as we decarbonise.

Coordination is necessary, but it appears exceedingly difficult at the same time.

Given the risks we face, this is sobering.

Fortunately, there are people working on these challenges already. I’d like to introduce you to one such group of visionaries.

The Internet of Energy Network: teaching toasters to fly

In 2018, Dr Adam Bumpus, Alex Evans, and Sim Wilson came together with a desire to tackle the challenges of energy coordination. If they could figure this out, they knew they could help the world move toward a brighter future.

One of their first questions was, “what if we could build coordination capacities into the things that already exist?” I appreciate their choice to ground high ideals in reality. Instead of pushing the grid to change, they started at the bottom with individual devices in homes and businesses.

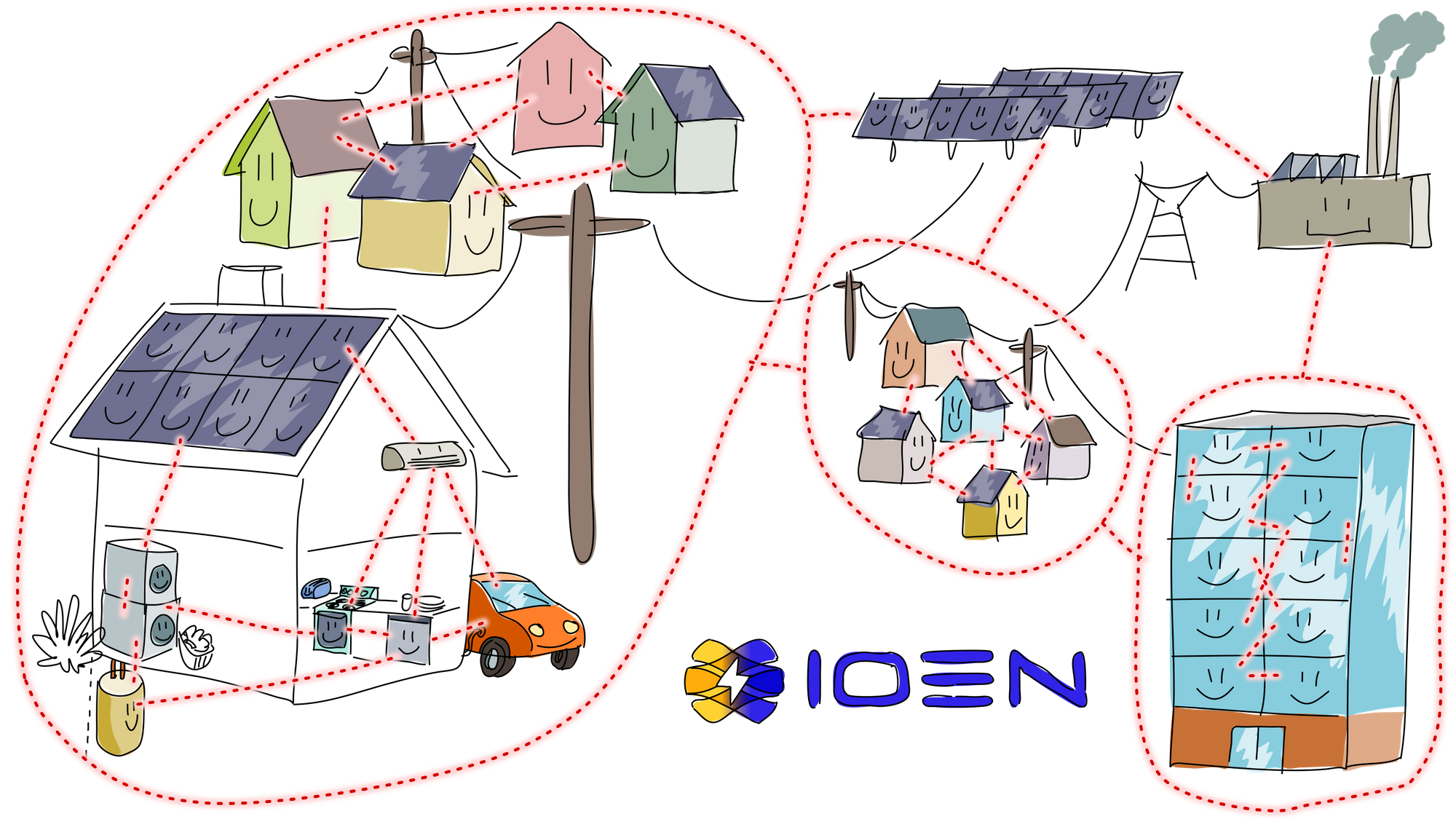

The trio called themselves RedGrid, assembling a team to help them imagine ways to get all these devices talking to each other. They asked what would happen if they were to connect together into ‘virtual microgrids’ and eventually into a global ‘software-defined grid’ giving intelligence to the existing physical grid. Production and storage devices, side by side with our air conditioners and fridges and ovens, making decisions together in response to changes in supply and demand. Just like a flock of starlings.

Mike Gamble, the company’s lead architect, describes this approach as “grassroots, bottom-up, organic.” Anyone who wants to join the flock is welcome.

As they built out this vision, they called it the Internet of Energy Network (I’ll call it IOEN, pronounced “ion”, for short). Given what I learned about the inflexibility of the current energy grid, this approach makes a lot of sense. It won’t require everything to change at once, which means that it has a chance of actually working. Regardless of how many people and organisations end up getting involved, something meaningful can happen at every scale. As more layers are added, the benefits start compounding.

And it happens to mesh nicely with the greenest, least complicated carbon reduction technique: just use less energy.

Even without taking advantage of the IOEN, RedGrid has an app that talks to smart appliances (and not-so-smart appliances using smart plugs). At its most basic, it helps people monitor their energy consumption; this alone has been shown to reduce people’s consumption patterns.

It also allows people to schedule energy-hungry appliances, like their dishwasher, in the middle of the day when green energy is plentiful. This doesn’t reduce consumption by itself, but it can help them green the energy they do consume, or get better rates and even rebates by taking advantage of their energy company’s demand response incentives. This doesn’t just save people money and make them feel good; it also prevents more infrastructure from being built. Remember that power companies build to meet peak demand — if we can flatten the peaks, the grid can be leaner.

Their software can also use machine learning to help long-running machines, such as air conditioners and pool pumps, use less power without sacrificing comfort.

If everyone added this sort of smarts to their individual energy use, we’d likely see both consumption and peak demand start to drop across the world. It’d help — to an extent. But the RedGrid team thinks that the real reductions will happen when these devices can break through the four walls around them and start talking to their neighbours.

Devices in the IOEN will be able to emit signals for other devices to respond to. At noon the community solar farm could say “we’re flooded with energy right now; can anyone use it?” Hundreds of dishwashers and car chargers, waiting for just such a signal, would turn on in response. Or in the evening the utility could say “we’re getting stressed; could everyone go easy for a while?” and air conditioners, pool pumps, and water heaters would scale back.

It gets more interesting when devices, and the people who own them, can talk directly to each other. Rather than overwhelming the community solar farm all at once, all those dishwashers could arrange to take turns. Or, if someone knows they’re going to be using a lot more electricity than usual — maybe they’re cooking for a big birthday party — they could let their neighbours know. People like being neighbourly, so they’re likely to make accommodations for that. Mike suggested that it could even spur a bit of friendly competition among virtual microgrids, an energy-saving drive: “You may have a group that is your sports team, and you are aiming to do better energy-wise against another team.”

And with the increase in local generation and storage — rooftop solar and electric car batteries — energy consumers could also be providers, selling their surplus to their neighbours. Local generation reduces the burden on infrastructure even further and makes everyone more resilient to power outages.

The IOEN is simply the communication layer that makes all this possible; the real magic happens in the applications built on top of it. RedGrid sees more opportunities on the horizon.

- Virtual microgrids can aggressively optimise their energy use, offer their combined optimisations as a package to energy companies, and distribute the rebates to members.

- Physical microgrids such as Monash University’s Net Zero project (partnering with RedGrid) can build smaller systems if they can rely on the IOEN to help smooth out demand peaks.

- If grid operators and power producers choose to use aggregated, anonymised data from individuals and virtual microgrids, they can do an even better job of planning, building out, and maintaining their infrastructure.

- As the network grows, third-party service providers can pop up, offering intelligence and insights to help everyone reduce their energy use even further.

- Equipped with IOEN-based management software, new microgrid projects could receive investor money in exchange for a stake in revenues, accelerating the adoption of renewables.

The Rocky Mountain Institute calls this demand flexibility, predicting that it can reduce energy-related emissions by up to 40% as energy electrifies and decarbonises. But they see electricity pricing as the main coordination tool. RedGrid’s vision for the IOEN embraces pricing but goes beyond it, giving us a way to coordinate directly and explicitly with each other.

Why decentralisation?

Good question. Decentralised coordination is messy and awkward. If you’ve ever tried to organise a multi-family camping trip, you know what I’m talking about.

First of all, when we’re dependent on faraway, centralised infrastructure and all the stuff that connects us to it, we’re in a vulnerable position. This goes for both electricity generation and the digital tech needed to make it ‘smart’. What if the power plant, the machines in the data centre, or any of the miles of wiring between them and our town, go offline (or even burn down)? Suddenly we’re stranded. With rooftop and community solar, home batteries, and edge computing, we have the means to stay online, right in our home town.

Second, the further away the power source is from your plug, the more energy is lost. It’s not a huge deal, but local generation does come out a little bit ahead.

Lastly, the rising complexity of the modern grid, along with the decisions we need to make, will virtually demand it. Zillions of new internet-connected plugs, toasters, solar panels, and car chargers will be coming online, producing lots of data and expecting to be able to make split-second decisions based on current local conditions. This is a logistical challenge for cloud computing, which (despite its fluffy name) happens in faraway data centres. It’s going to be hard for the cloud to keep up. (And I ought to point out that it has its own ecological problems too).

Where Holochain comes in

This is the Holochain Blog, after all, so I ought to mention it. Why did RedGrid build the IOEN on Holochain? The way Mike explained to me, it’s because Holochain is built for decentralisation.

And I’m not talking about the sort of decentralisation you see in blockchain. It’s a marvellous feat of engineering with some compelling use cases, but it’s still logically centralised, according to Ethereum’s creator Vitalik Buterin.

In practice, that means that your smart devices need to be connected to the global blockchain network all the time. This demands an always-on internet connection with zero downtime — which is fine if that’s what you have, but it’s problematic if you’re part of the world’s majority who live with patchy power and internet.

First-generation blockchains are also unfit for tiny smart devices, and they consume a massive amount of electricity for very little work (although newer DLTs are addressing those problems). The solution shouldn’t contribute to the problem. Mike tells me that “we turned our backs on Ethereum years ago”.

Holochain was designed to tolerate messy, unreliable connectivity. Far from being an anomaly, this may become increasingly common. During our local wildfire season, one fire nearly knocked out power and internet for 60,000 people. This would not have been a problem for an IOEN-powered local grid.

Holochain’s creators built it for edge computing in the extreme. Every device carries its own weight, according to its ability. It stores its own data, makes its own decisions, connects directly to neighbouring devices, and helps support the health of the local network. This lets the computing capacity scale linearly with the number of participants. And less powerful devices will soon be able to offload their work to a decentralised cloud if needed.

Mike and his colleagues also appreciated that Holochain already had a small but strong developer community. In preparation for an IOEN demo for their partner Monash University, Holochain developers from around the world rallied around RedGrid to make it happen. After the demo, Mike said:

“I should point out that what attracted me to Holochain was the support, not so much the tech. And it’s just in the last month that this has proven out, with Guillem and Connor [and Alfredo, Jesús, and Eduardo] helping us… You can see in GitHub and Discord their discussions with David Meister and Tom Gowan [Holochain core devs], to the point where a community dev actually found things and updated the core. It’s really pretty impressive. And Monash recognised that.”

Adam agreed, saying,

“And that was really cool, because you’re building together. For us as a company, we’ve had lots of good support from Art [Brock] and Eric Harris-Braun [Holochain co-founders] from the beginning, and obviously other people Mike mentioned... It makes us feel good—about the community, about the whole mission, and also there are other people out there who are not building on Holochain but believe in what we’re doing, the Holochain/RedGrid combination.”

Where you come in

When we’re faced with the stark challenge of climate change, and the apparent inaction of the people who make decisions, it’s easy to fall into discouragement. Many of us are desperate to see change, but feel powerless to actually make the change happen. We would seize any opportunity to get our agency back, to help guide our world towards a happy future.

And we technologists have often found ourselves part of the problem rather than the solution. But projects like this remind me that there is a place for appropriate applications of technology, there is a role for people who can design, program, build, tinker, and tweak. We can “create options for policy-makers”, in the words of Saul Griffith. And when they ignore those options, we can step around them and build tools for everyone — tools for coordination, tools to make the invisible visible. Tools to help us make sense of our world and take action together.